The Healthy Relationships Project ®

School-based Programs Empirical Basis and Evaluation Results

The Healthy Relationships Project ® has school-based programs that are health-based, developmentally-appropriate, safety-supported childhood sexual abuse prevention curriculum that includes faculty and staff training; parent events; parent newsletters for each lesson; and student lessons. The HRP has four components: Care for Kids (Pre-K to 2nd Grade); We Care Elementary (3rd grade to 6th grade); SAFE-T (7th and 8th grades); and Project SELFIE (7th to 12th grades).

-

Care for Kids topics include communication skills, nurturing skills (empathy), body parts, developing positive attitudes toward sexuality, and understanding of healthy boundaries. The student lessons reflect the way children learn at this developmental phase through activity. Each of the six lessons lists the National Health Standards that are covered in the lesson.

-

We Care Elementary topics include self-esteem, support systems, asking for help, understanding feelings, responding to feelings, empathy, body language, personal boundaries, respecting other’s boundaries, coping and accepting no, sexuality, sexual harassment, and adult support. The lessons include activities to anchor the concepts. Each of the six lessons lists the National Health Standards that are covered in the lesson.

-

SAFE-T (Sexual Abuse Free Environment for Teens) topics include support; coping; empathy; respecting boundaries; flirting, joking, and sexual harassment; taking responsibility; and bystanders. The lessons are interactive, and a final project for each grade level encourages student creative learning. Each of the 10 lessons for 7th grade and 10 different lessons for 8th grade lists the National Health Standards that are covered in the lesson. This curriculum has been rigorously evaluated, click the button below to learn more.

-

Project SELFIE (Safe Expression onLine for Internet Empowerment) topics include the destinction between consent, cooperation, and compliance in digital interactions; the laws on sexting by minors; how to cope with peer pressure; ways to respond to requests to sext; ways to respond to unsolicited sexts; and how to be an empowered bystander. Through two interactive, developmentally appropriate, and trauma informed presentations, youth learn how to prevent sexting and respond to concerning digital communications. This program also includes an adult training for parents, caregivers, and adults who work with children such as school personnel or professionals at youth serving organizations. This two-hour long, interactive, and trauma informed adult training, called Project SELFIE: Keeping Youth Safe on the Internet, prepares adults to protect youth from adolescent sexting, online grooming, online pornography, and in person acquaintances of youth who use digital communications as a grooming tactic. This program is empirically-based, developmentally appropriate, and trauma informed.

Information on Dr. Marcie Hambrick’s invited presentation on the empirical basis and evaluation results at the 2023 Together for Prevention Conference can be found here.

Note: Project SELFIE can be used as an add on to SAFE-T or as a stand alone program.

Widespread Usage

In the U.S., the child sexual abuse prevention programs of Prevent Child Abuse Vermont have been utilized in 39 states and in Washington D.C., as well as in multiple sovereign tribal nations (Navajo Nation, Sitka Tribe of Alaska, Arapaho Tribe, Apache Tribe, and the Senaca Nation). Additionally, it has been used in these countries: Canada, Iran, Honduras, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates. This illustrates the versatility of the programs for various communities! The Healthy Relationships Project is recognized as a promising strategy for international communities to decrease child sexual abuse by The Eradicating Child Sexual Abuse Project.

The Healthy Relationships Project’s school-based programs have been utilized in 38 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

Evaluation Study Underway

Northeastern University, funded by the CDC, is evaluating Care for Kids © and We Care Elementary ©. The study is in the final year of 4 years of implementation. Click for more.

Empirical Basis of the Components of HRP

Child Sexual Abuse Prevention Approach: Scholars suggest that child sexual abuse prevention that is effective must take a public health approach. “The goal of primary prevention is to prevent a problem from ever occurring, and services are offered to everyone, regardless of risk status” (Wurtele, 2008).

The HRP is a public health, universal dosage approach to child sexual abuse with the primary purpose of preventing it from occurring in the first place. It is a community level approach that engages many of the adult gatekeepers who are tasked with promoting safe environments for children. School professionals and staff as well as parents and caregivers receive empirically driven interventions that promote the protective factors proven to reduce incidences of child sexual abuse. Additionally, given that 30-50% of child sexual abuse is the result of child-to-child interaction (Finkelhor, 2009), students receive lessons to promote positive social emotional skills that create healthy relationships with peers.

Faculty and Staff Training: Research indicates that schools in the U.S. are sites of sexual harassment for children (Hill and Kearl, 2011). For teachers, survey results indicate that child maltreatment, including sexual abuse, was covered by routine trainings internally in schools, however intervention skills (primary prevention) were given much less attention than secondary and tertiary forms of after-the-fact reporting (Abrahams, Casey, and Daro, 1992). Secondary prevention training focuses responsibility for protection with governing authorities, such as child protective services or law enforcement, two authorities that cannot act prior to harm to a child, which could hamstring school personnel’s ability to take action during the grooming phase. Weak community sanctions contribute to higher incidences of sexual violence in society (WHO, 2012). Additionally, research indicates that organizational tolerance of adult boundary violating behaviors contributes to sexual abuse of children and that a wholistic approach including staff at all levels is protective (Roberts, Sojo, and Grant, 2019).

The HRP raises school personnel’s understanding of primary prevention action steps and centers the locus of control with the school personnel (cafeteria workers, janitors, paraprofessionals, educators, and administrators). Staff, faculty, and administrators of schools learn to identify pre-offending, boundary violating grooming behaviors and the action steps to address these instances. Administrators are encouraged to review policy around pre-offending, boundary violating grooming adult behaviors and are provided with information on best practices for dealing with instances.

Parent Events and Parent Newsletters for Each Lesson: Research indicates that prior to prevention interventions on risks to children from child sexual abuse parents had minimal knowledge (Elrod and Rubin, 1993) or were misinformed. Studies show that parents underestimate the prevalence of child sexual abuse, believe that being a boy is a protective factor, believe that young children are not at risk, believe that those who harm children sexually are somehow easy to spot and would appear vastly different from other adults (Finkelhor, 2009; Wurtele and Kenney, 2010; Bernier and America, P.C.A., 2015; Letourneau et al., 2014). When offered prevention interventions, parents are receptive to learning more about child sexual abuse (Wurtele and Kenney, 2010), and can learn and retain information about child sexual abuse prevention (Wurtele, Moreno, and Kenney, 2008; Renk et al., 2002). But, it is important to recognize that many child sexual abuse prevention programs for parents to date have focused on teaching children to protect themselves from child sexual abuse or relied heavily on secondary prevention strategies, which disregards the power structures between children and adults, the nature of the dependency of children on adults for basic safety needs, and the developmental abilities of children (Rudolph, 2018; Finkelhor, 2009). Additionally, for the 30 to 50% of child sexual abuse that is due to child-to-child interaction (Finkelhor, 2009) low parental supervision was a risk factor while support systems and parental monitoring are protective factors (Letourneau, 2017; Basile, et al., 2018).

For this reason, the HRP parent components address common myths by providing parents with accurate information and teach that adults are responsible for protecting children from sexual abuse. Parents gain the skills to carefully monitor children, particularly in gatherings between children of different ages, developmental stages, or power differentials. Additionally, parents are trained to recognize grooming tactics in other adults and to respond by keeping children’s environments free from grooming and sexual abuse.

Student Lessons: Research has shown that children who exhibit harmful sexual behaviors that result in sexual abuse of other children have worse emotional intelligence than their peers, have low sex knowledge, lack boundaries, and experience more social problems. (Fernández-González, et al., 2018; Kwiatkowski, in press). Children can learn social emotional skills (Diekstra, et al., 2008).

The HRP promotes positive social emotional skills in children at each developmental stage by building skills through active learning. The lessons build emotional intelligence and promote empathy and healthy boundaries. In addition, the lessons encourage help seeking behaviors by guiding children to recognize and communicate with a trusted adult. Additionally, older students receive lessons with health-based, developmentally-appropriate information on sexuality. The oldest students receive information about avoiding sexually harassing behaviors and being an engaged, caring bystander if someone’s boundaries are crossed.

Author: Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

Care for Kids©

(Pre-K to 2nd Grade)

SaFE-T External Evaluation

SAFE-T (Sexual Abuse Free Environment for Teens) © external evaluation results show that students gained and retained knowledge dispelling sexual myths. Additionally, compared to the control group students had lower rates of dating violence and of sexually harassing behaviors.

Safe-T Expernal Evaluation

SAFE-T (Sexual Abuse Free Environment for Teens) © external evaluation results from a study conducted in Hartford Connecticut

Vermont’s Success!

As the map demonstrates, Vermont’s implementation of the Healthy Relationships Project is widespread and has been ongoing for three decades with measurable improvement!

Evaluation Results: Healthy Relationships Project ©

Faculty and Staff Training in Schools and Head Starts

From 2014 to 2018 N=276

Summary: Faculty and Staff self-rated own pre / post knowledge and skills using the following categories Below Average, Average, Above Average, Excellent. Results show statistically significant improvement on all constructs. Each chart below shows self-rating of pre condition in blue and after training in burgandy.

Paired T-test: t= -18.524; df = 274 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T-test: t= -18.891; df = 272 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T-test: t= -14346; df = 267 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T-test: t= -12.075; df = 271 P = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

From 2017 to 2018 N = 75

Paired T-test: t= -9.034; df = 73 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

From 2014 to 2016 N = 203

Paired T-test: t= -11.464; df = 193 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Analysis conducted by: Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

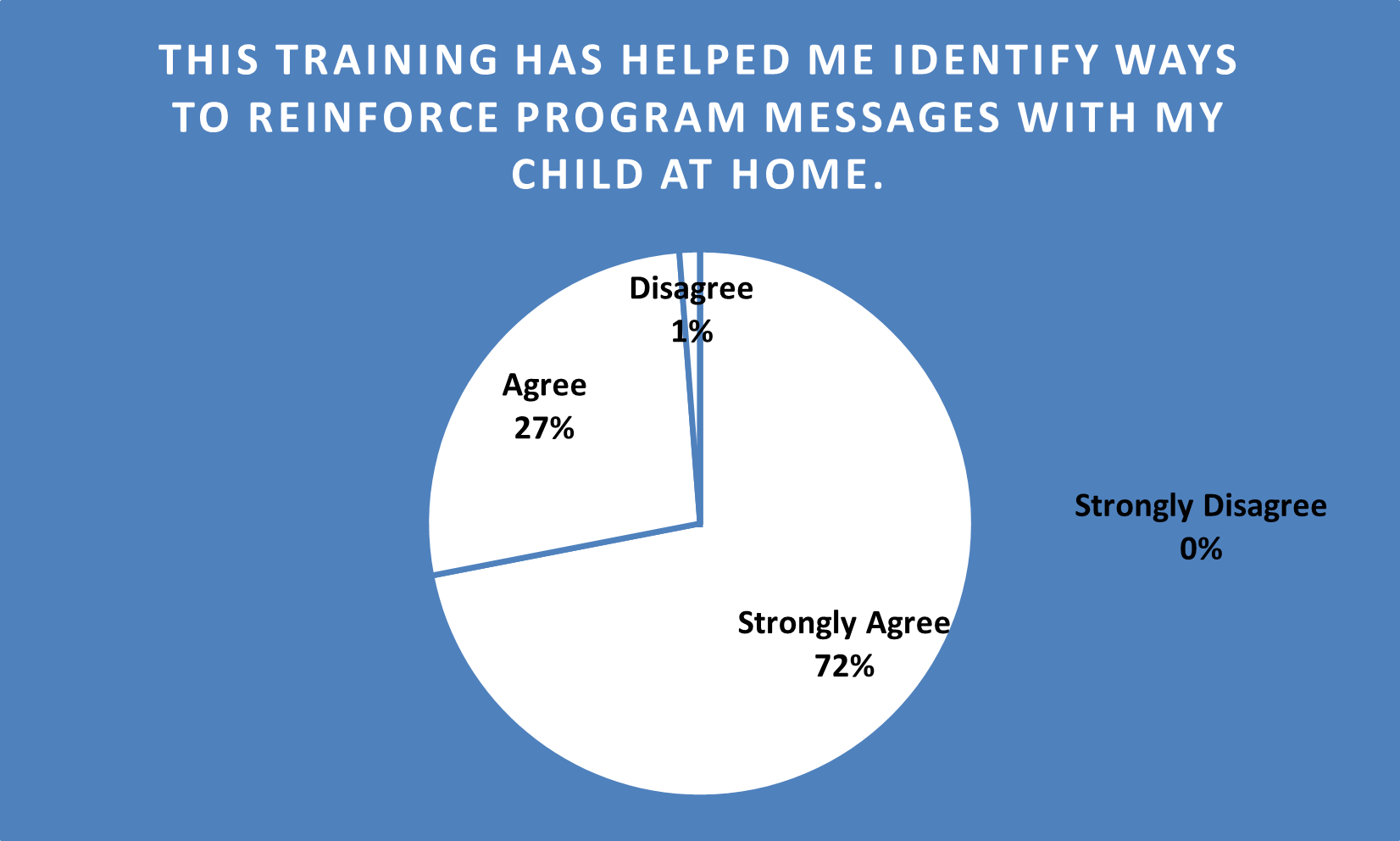

Healthy Relationships Project © Report of Parent / Caregiver Event Evaluations from 2017 to 2018

84 Parents Attended

Summary: Parents who attended a parent event were asked to evaluate the training using the categories Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Agree.

Summary: This graphic reflects that after attending the Healthy Relationships Project Parent / Caregiver Event 100% of parents / caregivers felt their knowledge of the Healthy Relationships Project program had improved and of these, 90% of them strongly agreed.

Summary: This graphic reflects that after attending the Healthy Relationships Project Parent / Caregiver Event 98% of parents / caregivers felt their knowledge of child sexual abuse had improved and of these, 63% of them strongly agreed.

Summary: This graphic reflects that after attending the Healthy Relationships Project Parent / Caregiver Event 99% of parents / caregivers were prepared to provide child sexual abuse prevention messages at home.

Summary: A group of 17 attendees were asked this item. Of these, 100% understood the connection between social / emotional skills and sexual abuse and among these, 67% strongly agreed.

Summary: A group of 39 attendees were asked this item. Of these, 95% felt prepared to promote healthy relationships with their child and among these, 54% strongly agreed.

Summary: A group of 16 attendees were asked this item. Of these, 100% were more aware of resources and among these, 75% strongly agreed.

Summary: A group of 17 attendees were asked this item. Of these, 100% rated the presenter as effective and among these, 83% strongly agreed.

Summary: A group of 17 attendees were asked this item. Of these, 100% rated the training as useful and among these, 76% strongly agreed.

Report Compiled by Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

Care for Kids (Pre-K to 2nd Grade)

Student Assessment Results 2020 - 2024

Evaluation Results Between April 6, 2020 and July 3, 2024

N=160

Summary: Classroom teachers assessed student abilities in the healthy relationship skills prior to the first lesson and after the sixth lesson. The teacher rates all children using a Likert scale.

Students were from three states, Vermont (87%), New Hampshire (7%), and Virginia (6%).

Paired T Test: t = 4.252 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 5.554 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 5.739 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 4.375 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 5.698 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 7.596 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 6.680 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 3.905 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Paired T Test: t = 5.186 df = 159 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Analysis conducted by: Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

We Care Elementary © Analysis of Student Assessments 2015 to 2018

116 Students in 4th Grade Completed Six Lessons

Summary: Classroom teachers assessed student abilities in the healthy relationship skills prior to the first lesson and after the sixth lesson. The teacher rates all children as Never, Rarely, Frequently, or Always utilizing the skill. Each chart below shows teacher rating prior to lessons in blue and after six lessons in green.

Analysis by Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 83% of students were frequently or always asking for help when needed (compared to 64% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -5.216 df = 104 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 82% of students were frequently or always expressing their emotions with words (compared to 63% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -4.588 df = 104 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 84% of students were frequently or always coping with strong emotions with words (compared to 70% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -3.661 df = 99 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 84% of students were frequently or always expressing their emotions with words (compared to 70% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -3.661 df = 99 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 92% of students were frequently or always communicating personal boundaries to others (compared to 79% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -2.004 df = 105 p = .048 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 92% of students were frequently or always respecting others’ boundaries (compared to 79% prior to the lessons).

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -1.478 df = 105 p = .142

Analysis conducted by: Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

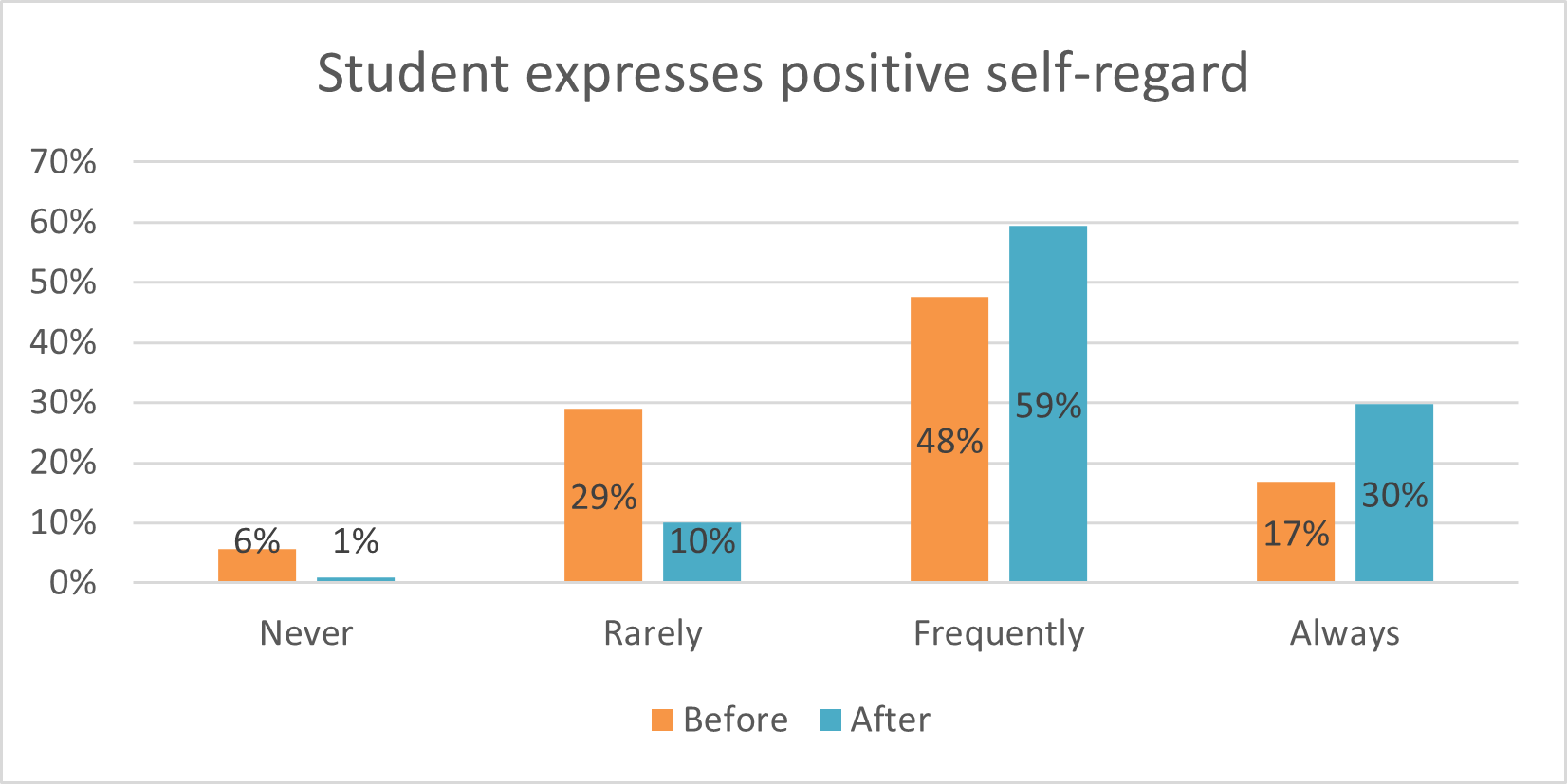

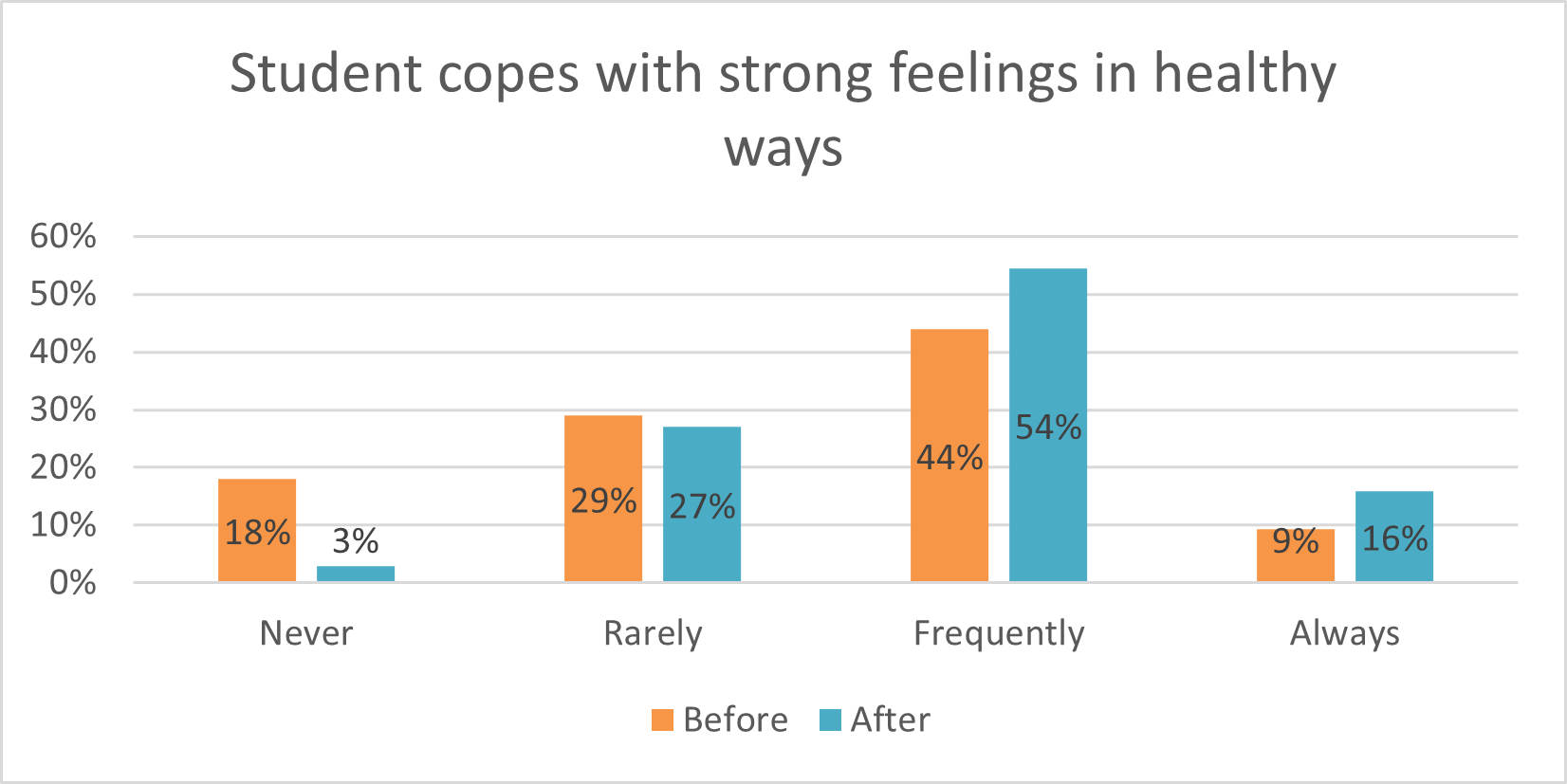

We Care Elementary © Analysis of Student Assessments 2017 to 2018

111 Students in 3rd Grade Completed Six Lessons

Summary: Classroom teachers assessed student abilities in the healthy relationship skills prior to the first lesson and after the sixth lesson. The teacher rated all children as Never, Rarely, Frequently, or Always utilizing the skill. Each chart below shows teacher rating prior to lessons in peach and after six lessons in aqua.

Analysis by Marcie Hambrick, PhD, MSW

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 89% of students were frequently or always expressed positive self-regard (compared to 65% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -4.008 df = 95 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 80% of students were frequently or always expressing their emotions in words (compared to 58% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -3.604 df = 97 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 90% of students were frequently or always asking for help when needed (compared to 65% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -4.260 df = 97 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 70% of students were frequently or always coping with strong feelings in healthy ways (compared to 53% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -3.278 df = 95 p = .001 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 88% of students were frequently or always responding to others’ non-verbal cues (compared to 64% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -4.296 df = 99 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Summary: This graphic reflects that after six We Care Elementary lessons 74% of students were frequently or always asking to confirm others’ feelings when in doubt (compared to 53% prior to the lessons). This is statistically significant improvement.

*Aggregated student results among children in which there was an observation by the classroom teacher

Paired T Test: t = -4.441 df = 97 p = .000 (Statistically Significant Improvement)

Project SELFIE © Analysis of Student Pre and Post Tests 2022

References

Abrahams, N., Casey, K., & Daro, D. (1992). Teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about child abuse and its prevention. Child abuse & neglect, 16(2), 229-238.

Basile, K. C., Rostad, W. L., Leemis, R. W., Espelage, D. L., & Davis, J. P. (2018). Protective factors for sexual violence: Understanding how trajectories relate to perpetration in high school. Prevention science, 19(8), 1123-1132.

Bernier, J., & America, P. C. A. (2015). State and federal legislative efforts to prevent child sexual abuse: A status report. Prevent Child Abuse America. Chicago: www. preventchildabuse. org.

Diekstra, R., Sklad, M., Gravesteijn, C., Ben, J., & Ritter, M. D. (2008). Teaching social and emotional skills world-wide. A meta-analytic review of effectiveness. Social and emotional education: An international analysis, 49, 255-312.

Elrod, J. M., & Rubin, R. H. (1993). Parental involvement in sexual abuse prevention education. Child abuse & neglect, 17(4), 527-538.

Fernández-González, L., Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Echezarraga, A. (2018). The role of emotional intelligence in the maintenance of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 68-73.

Finkelhor, D. (2009). The prevention of childhood sexual abuse. The future of children, 169-194.

Letourneau, E. J., Eaton, W. W., Bass, J., Berlin, F. S., & Moore, S. G. (2014). The need for a comprehensive public health approach to preventing child sexual abuse.

Letourneau, E. J., Schaeffer, C. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Feder, K. A. (2017). Preventing the onset of child sexual abuse by targeting young adolescents with universal prevention programming. Child maltreatment, 22(2), 100-111.

Roberts, V., Sojo, V., & Grant, F. (2019). Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport Management Review.

Rudolph, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Shanley, D. C., & Hawkins, R. (2018). Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk. Child maltreatment, 23(1), 96-106.

Wurtele, S. K., & Kenny, M. C. (2010). Partnering with parents to prevent childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Review: Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, 19(2), 130-152.

Recommended Citation:

Hambrick, M. (2024). The Healthy Relationships Project ® Empirical Basis and Evaluation Results. Prevent Child Abuse Vermont. https://www.pcavt.org/hrp-empirical-basis